Freight on Track for Major Growth?

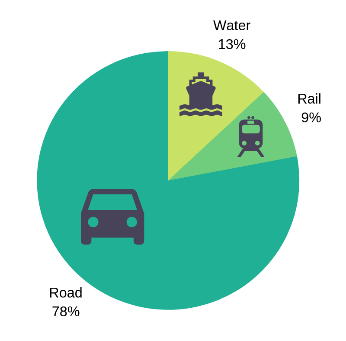

Rail freight contributes £870m to the economy and plays a big part in reducing congestion and carbon emissions, with each freight train removing about 60 HGVs off the road. However, it represents only a small part of the total freight movements. While rail traffic, particularly intermodal traffic has grown since the mid-90s, with one in four sea containers arriving at UK ports now carried inland by rail, the total proportion of goods carried by rail freight is not as important as it could be.

Figure 1: Domestic Freight Traffic by mode: goods moved 2017

When size matters

The flexibility that road freight offers with a door to door service, together with lower entry and labour costs, make it more challenging for rail to compete over short distances. Rail requires loading and unloading facilities at terminals at either end of the journey before the goods can be transported by road to the end user. It has been calculated that rail freight becomes competitive on distances over 300 km.

Furthermore, the UK rail industry faces the legacy issue of its existing infrastructure, much of which was designed and built for another age. Many of the UK’s bridges, tunnels and stations are small in comparison to international standards, which limits the size of containers that they can handle or necessitates the use of specially designed lower rail wagons. Rail networks on the European continent can generally cope with larger boxes, as well as trailers and HGVs, while the US rail network can accommodate double stack containers. Newer parts of the UK network (such as HS1 and HS2) are being built with larger tunnels and bridges but, for now, this only covers a small part of the country, and the access charges are high.

Figure 2: Double stack container freight train (image courtesy of Simeon87 under Creative Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0) licence)

There are also related capacity challenges, exacerbated by the parallel desire to keep increasing numbers on the passenger side of the business. Additional capacity could be made available by increasing the size of bridges and tunnels on key freight routes, and by investing in other technical solutions such as faster freight trains, double stack containers and the conversion of high-speed trains to accommodate the transportation of parcels. But while greater capacity would certainly help, it cannot be the only answer. In an increasingly connected and high-tech world, the rail freight sector needs to stay up to date with the latest commercial trends and technological advances – or risk losing out to other modes of transport.

The imperative of innovation

One such commercial trend that is affecting nearly all industries is the increased personalisation of services and the move by more businesses to minimise stock in order to keep costs low. The prevalence of ‘just in time’ inventory management has already transformed the way in which goods are manufactured, as well as the quantity and frequency in which they are moved. This in turn has created a need for responsive and flexible systems right across the freight and logistics sector.

Ensuring that systems remain responsive and flexible is clearly not easy in a sector where infrastructure is fixed and vehicles have long life-spans, but failure to evolve could see the rail freight industry lose out to road freight as well as to emerging new modes of transport, such as tube logistics and unmanned aerial vehicles.

Another trend spreading across industries combines increased automation and digitalisation with a view to embracing globally connected systems along the lines of the Physical Internet Initiative. As a result of this, the next ten years will likely see a greater adoption of automation within physical infrastructure and handling equipment at ports, airports and other logistics hubs.

Digital identifiers and blockchain technologies are meanwhile likely to spread through supply chains to improve the safety, security and traceability of goods in an automated environment. Again, rail cannot afford to just watch from the sidelines.

Shake-ups to trade and industry

Beyond the changes to physical infrastructure and the arrival of new technologies, there will also be a need to keep up and adjust to potentially major shifts in international trading arrangements. The Chinese government’s Belt and Road initiative is a striking example of how new initiatives can have sweeping effects on the way goods are transported globally, with trial deliveries of goods from the UK to China along the road and rail route already achieving transit times of 12-18 days – around a third of the time that it would take to transport the same goods by sea.

The logistics industry is also going through a period of consolidation. We have already seen some of the largest carriers merge with forwarders to have more control over end-to-end operations. It is possible that more online retailers will follow Amazon’s lead and create their own logistics operations in order to reduce supply-chain costs.

The keys to future success

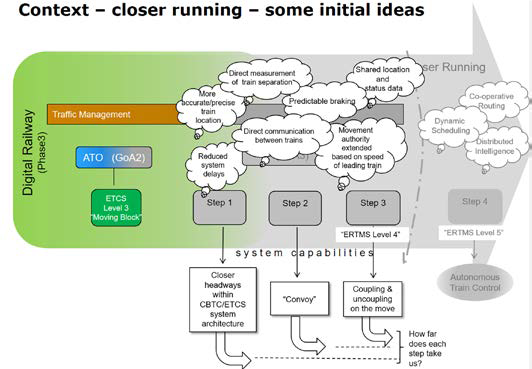

Flexibility can be improved through the urgent development of an effective digital railway strategy that is supported by intelligent and dynamic timetabling techniques to allow freight paths to be booked more rapidly and reliably.

Figure 3: Initial ideas to support a “closer running” concept aimed at enhancing capacity on the UK rail network, without compromising current ‘safe separation’ principles – Source: RSSB research project Closer running (Reducing Headways) T1095

Where capacity is underutilised, there are new markets which could be attracted to rail overnight if the size of bridges and tunnels in the UK could be enhanced on key freight routes to accommodate larger boxes and trailers without the need for specially designed wagons. Some of these changes are unlikely to be either technically or economic viable in the short term, but a better understanding of these ‘pinch points’ and options for them is key. Consideration should also be given to technical advances and solutions such as operating faster freight trains, double stack containers and converted high speed trains to accommodate parcel traffic.

Technological innovation will still need to go hand-in-hand with more traditional efforts to maintain resilience in the network’s infrastructure, particularly along key freight arteries where capacity is currently constrained. Reliability is fundamental to the success of rail freight so, in the event of disruption, freight traffic must receive a fair treatment with other rail users, have sound underpinning timetabling, and the development of suitable diversionary routes.

If good progress (and investment) is made on all of these fronts, we are confident that rail freight will be able to compete more effectively with other modes of transport, building on partnerships with the road freight sector to offer attractive and high performing end-to-end solutions for logistics providers.

Our blog series has so far focused on the coming 5-10 years. Next week, CPC Senior Strategist Alfie Jackson will share his views and scenarios on what transport will look like in 2040.

Related links:

- Freight (TSGB04) Data about domestic and international freight transport, produced by Department for Transport

- IPIC 2019 - 6th International Physical Internet Conference

- RSSB News - Next generation of railway traffic management systems

- Splash247.com - Russia and China set up Arctic shipping joint venture

- Wall Street Journal - Amazon’s Freight Push Rattles Logistics Sector

- RSSB research project - T1095, Closer running (reducing headways)